- Home

- About Us

- The Team / Contact Us

- Books and Resources

- Privacy Policy

- Nonprofit Employer of Choice Award

The employment relationship has changed. In the not-so-distant past it could be argued that people were, in a very real way, defined by their job, sector, or career path — certainly economically, but also socially. To be an MD, an academic leader, the CEO of a large corporation, the head of a foundation, or achieve any of a number of other glamorized careers brought a social validation and prestige that augmented the financial freedom often associated with professionals at that level. We can say (kindly) that because of the almost aspirational nature of these careers, the individuals in these or similar leadership roles were seen as the primary voice of knowledge and experience within and beyond their organization — a figurehead as well as a functionary — in spite of the fact that, at its core, a leader’s best trait is often their capacity to facilitate growth for the employees working with and under them. It’s important to acknowledge, at least on a surface level, where we’ve been, because where we’ve since gone has in many cases bred toxic work environments poisoned by leadership that simultaneously demands of itself to know how to do every job in an organization better than its employees while refusing those employees opportunities for growth — particularly where such opportunities may occlude their own (perceived) celebrity. I speak from experience; I worked for one such organization in the not-for-profit sector.

The employment relationship has changed. In the not-so-distant past it could be argued that people were, in a very real way, defined by their job, sector, or career path — certainly economically, but also socially. To be an MD, an academic leader, the CEO of a large corporation, the head of a foundation, or achieve any of a number of other glamorized careers brought a social validation and prestige that augmented the financial freedom often associated with professionals at that level. We can say (kindly) that because of the almost aspirational nature of these careers, the individuals in these or similar leadership roles were seen as the primary voice of knowledge and experience within and beyond their organization — a figurehead as well as a functionary — in spite of the fact that, at its core, a leader’s best trait is often their capacity to facilitate growth for the employees working with and under them. It’s important to acknowledge, at least on a surface level, where we’ve been, because where we’ve since gone has in many cases bred toxic work environments poisoned by leadership that simultaneously demands of itself to know how to do every job in an organization better than its employees while refusing those employees opportunities for growth — particularly where such opportunities may occlude their own (perceived) celebrity. I speak from experience; I worked for one such organization in the not-for-profit sector.

At that point I was on the creative side, both running social media marketing as well as producing all in-house video. Over the course of my time at the organization I experienced the consistent belittlement of my own work and witnessed the constant belittlement of the work of individuals in virtually every other department, all under the framework of ‘we-could-do-this-better-but-we’re-too-busy-being-leaders-so-unfortunately-we-need-you… but-don’t-worry-you’re-replaceable’. These discouraging in-person interactions were only compounded by a culture of backbiting and gossip in which leadership would, essentially, compare whose employees were the worst that week and where opinion and perspective was treated with scorn and outright hostility. It would not be outside the norm for an employee to give input on a concept or project only to hear that their supervisor had been dragged into a room afterwards for a barrage of complaints because they, the employee, had the temerity to express a point of view that did not connect seamlessly with that of mid-to-senior leadership.

Sadly, to many people, this is all too familiar — or even ‘toxicity lite’. Even for myself, this new reality wasn’t such a departure that it was enough to force me out the door. In the end, the last proverbial straw was when the chief executive officer demanded that I drop out of a conference that I had been selected to speak at (ironically, on ethics in marketing) because, amongst their litany of reasons, “this is just a Mo branding exercise and I won’t support that.” Needless to say, I resigned, and yes, the talk was a success.

The employment relationship has changed. Toxic work environments are not new; while exploring the culture of backbiting and belittlement is certainly (extremely) important, it’s not a novel concept. However, the role of personal brand in the employment relationship is, I believe, one of those blank spaces where the employment map is still being filled in — because, the reality is, for many new entrants into any workplace personal brand is a real and active consideration. Many no longer see employment as simply a paycheck or fuel for their passion project, but as one of the many tiles making up their personal mosaic online and offline, and so employment becomes something to choose with care. Social media has made personal branding infinitely accessible, and so it is a strange and, frankly, broadly detrimental decision any time an organization chooses to ignore the role of brand in a prospective employee’s decision making. Worse still is an organization whose leadership understands (or at least acknowledges the existence of) brand and yet actively chooses to undermine opportunities to grow brand for their employees.

Becoming a leader, a CEO, a President, a Founder is an aspirational position, and one of the perks of these positions has traditionally been becoming the voice of your organization’s brand — and embodying all of the prestige that comes with it. You, the leader, take the stage at conferences. People fill auditoriums to see you speak and hear your wisdom. Your employees aspire to one day be you (or at least take your place). Nowadays, however, everyone has a platform or at least the potential for a platform, and conferences accept speakers with innovative ideas — not necessarily speakers based on title. As we continue to move through a marketing era where ‘speaking’ and being a ‘speaker’ is more in-vogue than it has been in a very long time, the traditional foundations of what is required to become a speaker or thought leader in your space (age, tenure, academic education, masculinity) are being eroded. With this, the metric for what is considered an ‘aspirational’ position has changed.

The evolved, and far more effective, response to this is, of course, to understand that a shift in environment demands a shift in self — and so a need to work actively on building a leader’s own personal brand. Unfortunately, too many leaders still fight to hold the sand that is the perceived intellectual authority of their position between their fists, dominating their employees under the model of ‘we-employ-you-therefore-we-own-what-you-do’ even when that thing goes beyond scope of employment. The truly tragic part is that, faced with this, far too many bright employees adhere to will of leadership even where that will has no place, whether it be out of fear of losing their position, their income, or self-doubt that if this great leader doesn’t think they have what it takes to do whatever it is they want to do, then do they really have it? The irony is that out of a misguided respect for leadership even when leadership is in the wrong, far too many employees sacrifice respect for themselves. This is particularly salient in the nonprofit sector where professionals are often drawn to a cause as much as the employment experience and so, where love of cause trumps every other motivation, the self-effacement that we already see in many within the not-for-profit sector is compounded by a desire to avoid conflict and an unwillingness to lose the connection to cause.

The challenge here is complex, and an immediate counterpoint to the argument for brand is that leaders have a responsibility to govern the narrative around the organization they lead — the organization’s brand. I, however, am skeptical of the counterargument that employees are out there, going rogue, expressing uninformed fringe ideas counterproductive to the mandate of their organization and therefore that the role of leadership is to be the warden of their employees’ opinions. Most rational employment practices hire for fit and alignment as well as for skill and so it is inherently contradictory to then take the baseline approach that all employees are intrinsically misaligned and that you, as leader, need to keep them in line — a perspective that harkens back to the 1960s theory on employee motivation stating that ‘work is inherently distasteful to most people and they will attempt to avoid work whenever possible’.

Again, the challenge here is complex, and made more-so by the fact that the motivations of the leader and the employee compete both externally and within themselves. Yet, if we are to build an understanding around this that respects the integrity of an organization’s brand, supports employees, and allows leaders to maximize their potential, it begins with acknowledging that ‘personal brand’ as a function of and influence on employment is here to stay. It’s not just trending for now; it is a reality of the employment relationship. Given that, leaders should be looking for employees whose brands align with that of the organization and, selfishly perhaps, even their own, such that all brands can grow collaboratively, together. In a recent LinkedIn post by Oleg Vishnepolsky, Global CTO at DailyMail Online and Metro.Co.Uk, he wrote “Your ex-employees are your ambassadors for life” — and that is as salient a point as I’ve read in some time. Through the application process, during their employment, and following employment, the narrative surrounding an organization and its leaders is fundamentally changed by an employee’s experience. It is, therefore, unfortunate that leaders still see employees as commodities to be owned and directed rather than nurtured and grown.

The lack of understanding and respect for the personal goals, ambitions, hopes, desires, and brand of employees is just one of the many insidious issues that contributes to toxicity in the workplace, however it’s also one of the least frequently discussed or addressed due, in large part, to a combination of the less tangible nature of the harm and that the consequence to employees affects them primarily at a career level. Moreover, looking at toxicity in the workplace, generally, the sad reality is that many organizations where toxicity is rampant internally continue to exhibit strong outcomes that bely the rot within. Yet, eventually that rot will spread to the surface and when it does, particularly in nonprofit, the final victims of the toxic work environment won’t be leadership, or even the employees, it will be the beneficiaries that the nonprofit purports to serve. That, to my mind, is the true tragedy.

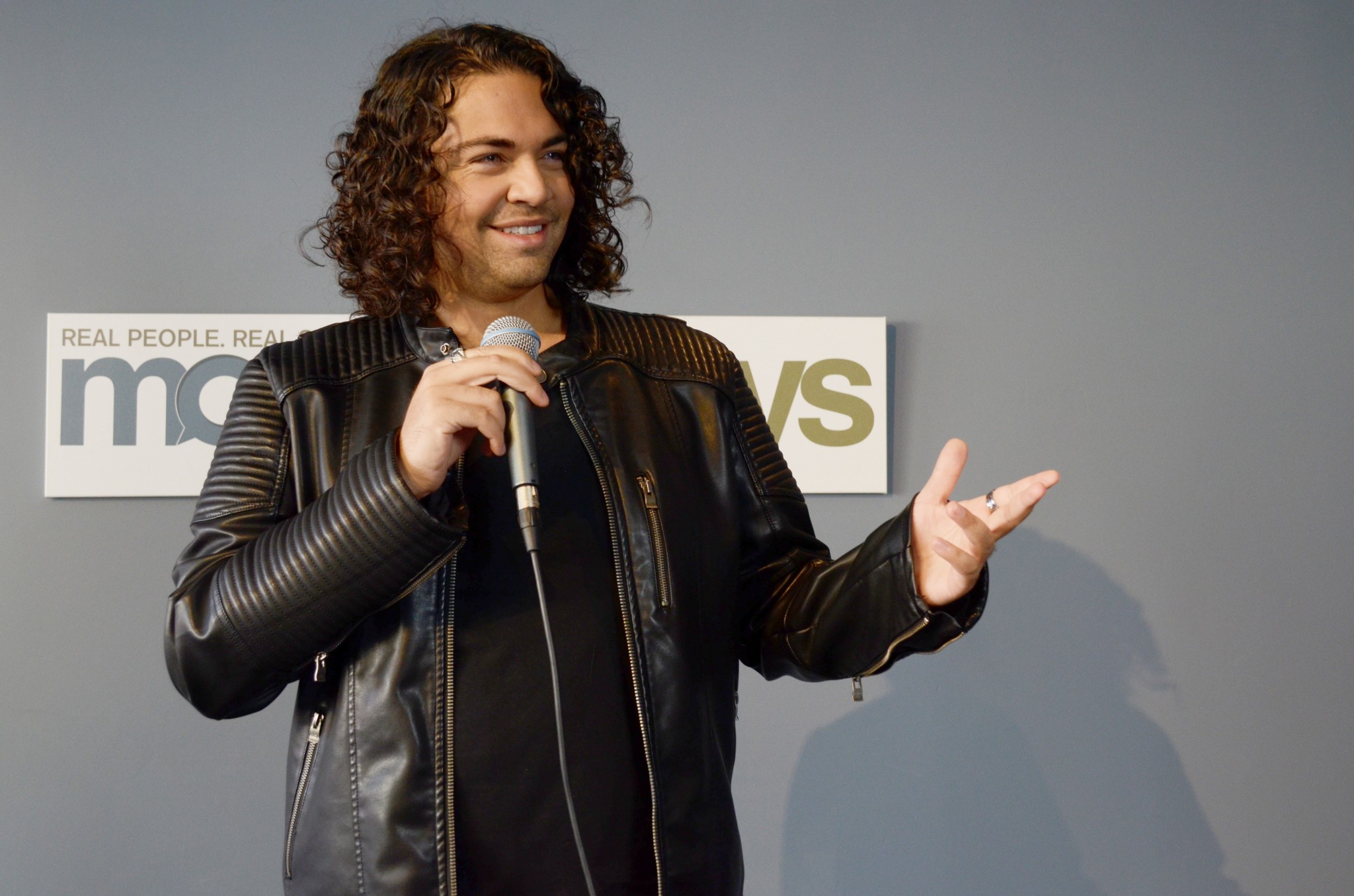

Mo Waja is a professional speaker, marketing storytelling expert, author, the Host of The Let's Talk Show podcast, and an Account Manager at Blakely. Mo has worked with not-for-profit, for-profit, and personal brands developing and implementing their digital storytelling strategy and, to date, has spent tens of thousands of hours coaching business professionals, advocates, post-secondary students, and medical practitioners in the art of professional speaking and communication.

Want more great content like this? Subscribe to Hilborn Charity eNews here and never miss another expert update.