- Home

- About Us

- The Team / Contact Us

- Books and Resources

- Privacy Policy

- Nonprofit Employer of Choice Award

Donors support nonprofit and charitable organizations that align with their interests and the pressing societal and community issues that concern them most. Some individuals and families possess wealth that allows them to give at extraordinary levels, creating an opportunity to make disproportionate impact in those areas.

Depending on their motivations and, often, the advice they get from professional advisors, fundraisers, and the organizations they are supporting, donors are sometimes presented with only two options:

• have their funds expended in the near term (e.g., helping pay for equipment or facilities that are needed now) or,

• have their gift invested for the long term, with the income generated used to provide funding for a purpose (e.g., scholarships or bursaries) that would go on indefinitely.

The latter approach involves creating an endowment fund. As donors contribute to the fund, they enjoy tax benefits, and as the fund grows over time, a reliable and steady cash flow is available for spending on charitable purposes.

Endowments continue to be a common method of investing donated funds, especially following the introduction and growth of donor advised funds (DAFs). Broadly defined, a donor advised fund is a charitable giving vehicle. It is initially established through an up-front donation by a donor (such as an individual philanthropist or family) to an independent organization (typically a foundation or financial institution). While the donor advises how the funds are distributed, all administrative, operating and governance matters remain the purview of the independent organization. While many DAFs allow for flexibility in how donor funds are invested and disbursed, by far the most common method is to create an endowment.

How endowments work

Several factors influence the growth and performance of an endowment, most notably the rate of return on the invested funds and the cost of administering the funds. Some endowments are also designed to not only maintain their initial capital value but to also grow over time, so payouts from them at least keep pace with inflation.

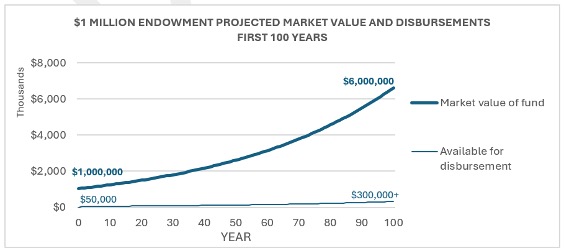

Consider the following example. Assume a donor makes a gift of $1,000,000 either directly to their charity of choice or via a DAF. For simplicity, also assume the full commitment is disbursed as a one-time lump sum (as opposed to pledging to fulfill the commitment through installments over multiple years).

That money will be invested in a manner that moderates risk, while at the same time is forecast to generate an attractive return. Given the history of such investments, it’s not unreasonable to assume that, on average, a fund will generate about 8% annually.

Now, let’s assume that the fund is designed to disburse 5% of its market value for use by the charity. Administrative and investment fees also vary, but for this example we will assume that together they amount to 1%. Any excess earnings will be reinvested in the fund to ensure that it has a chance to keep pace with inflation. (Note that the values used here will differ across charitable and other organizations that manage endowments on behalf donors and charities. These values have been chosen for illustrative purposes.)

Using these assumptions, the graph shows that an initial endowment investment of $1,000,000 is projected to grow to over $6,000,000 in market value after one hundred years. During this period, annual disbursements grow from around $50,000 per year to over $300,000 per year by year 100.

By the end of that century, the cumulative value of disbursements in this example will reach almost $15,000,000. It is hard to deny how impressive it is that a gift can generate 15 times its value in only one hundred years and keep on that trajectory forever.

If a donor’s intention is to ensure that there is always a steady and reliable stream of income available to support a certain charitable purpose, an endowment provides a suitable solution.

“Always” is a very long time

There's a caveat regarding the term "always" or its equivalents like "forever" and "perpetuity."

Donors have often been encouraged to fund an endowment intended to address issues and opportunities that they believe will be enduring, but as the world changes how certain can anyone be about what will be most relevant or useful hundreds or even thousands of years in the future?

Is it possible that by always the donor may really mean “in my lifetime” or “in my children’s/grandchildren’s/ great-grandchildren’s lifetimes”? How many generations into the future are they really concerned about? The answers to these and other questions should inform decisions about gift structures, and whether modifications to the typical endowment structure are sometimes warranted.

Part 2 in this series will further examine the pros and cons of endowments and the factors to consider to ensure that a donor and charitable organization are truly aligned in terms of what impact is targeted over what period.

Peter Fardy is Principal, Northport Philanthropic Advisory Services, and former Vice-President, Advancement, Dalhousie University. Contact him: peter@northportphilanthropic.ca