- Home

- About Us

- The Team / Contact Us

- Books and Resources

- Privacy Policy

- Nonprofit Employer of Choice Award

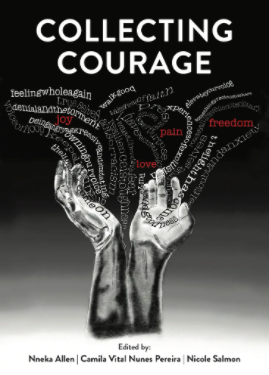

This is a collection and a documenting.

In it are the life stories of Black people. Black professionals who’ve spent the vast majority of their lives inspiring investment in social justice and change in the nonprofit sector.

We are Black fundraisers. And the reality is we live and work in the white world of philanthropy and charity. In these spaces, we are often the “first,” the “only” and the “other.” This “othering” links our experiences. We are bound together by our painful experiences of exclusion, denial and torment of anti-Black racism in our workplaces. But that isn’t all that binds us together.

These stories reveal, in living colour, the love we as Black people cultivate, and the joy that springs forth despite our pain. They illustrate the freedom we carve out for ourselves through courage and community. To understand our vivid narratives, the historical truths that undergird our current reality must be laid bare, and to decipher our voices, the culture from which they emerge must be acknowledged and understood. From context comes understanding.

Before Europeans arrived in the late 15th century, First Peoples, the Indigenous people, called North America Turtle Island. Europeans set about taking a wrecking ball to all indigeneity, killing, pillaging and colonizing First Peoples, and pitting Indigenous people against each other, ignoring tribal cultures and decimating sacred spaces. Meanwhile, they were also forging their merciless plot to traffic Black bodies across the Atlantic Ocean. Those Black hostages and their children became human fuel for the economic engine of what is today Canada and the United States.

The invaders brought their Spanish, French and British cultures with them, and for centuries, “settled” in various areas of the Continent. The English and French dominated, proclaiming the superiority of their cultures over Black and Indigenous peoples, and the English became the governing colonial force on the Continent until ousted by America in 1783.

Not so, however, in Canada, where the English settlers in Canada held dear to British colonial rule. Nor in Quebec, where the predominantly Catholic Quebecois in large number contested Protestantism and English colonial culture. The shared and prevailing cultures in this land, nevertheless, had become both French and English.

During the fervour of the 18th century’s Age of Enlightenment, pseudo-science breathed life into the idea of the racial and cultural superiority of Europeans. It wasn’t until then, when the European powers began mixing science and empire, that the idea of the supremacy of light skin over dark was created. That idea of essential superiority laid the foundation upon which the culture of all of North America was formed. In fact, Canada and the United States share the same history and culture, and their national stories are inextricably intertwined.

North America is the world’s third-largest Continent, beginning at the Arctic Circle and extending south to the Caribbean. No oceans divide the landmass, and the largest regions are the United States and Canada. Only in the last 174 years have these countries been separated by the 49th parallel—an arbitrary line born of politics and economics and in 1846 legally drawn by the Treaty of Oregon.

When the Europeans arrived in North America, there was no border to consider. People of shared backgrounds moved freely back and forth between countries, and loosely-controlled border checkpoints were not established until 1914. Otherwise, the rest of the extensive border remained unguarded2 until the tragic events of 9/11 fundamentally impacted that liberty of movement.

Today, the 49th parallel notionally serves to separate two national cultures perceived to be distinct. One culture thought to be brash, bold and historically oppressive. The other seen as “nice,” peacemaking and welcoming to everyone. Closer inspection of the history of this Continent, however, shows that, in the most important ways, the differences are actually more fanciful than real. In fact, they share the same imported dominant cultures, one landmass, an arbitrary border and the development of a massive economic engine—slavery.

The proliferation of plantation slavery in the Southern United States was a function of economics, geography and environment. Cotton transformed the American economy. The rich and fertile land of the South was perfect for such crops as cotton, tobacco and sugar, which drove the demand for more slaves.

The factors fostering the intense use of slave labour in the South did not exist in either the American North or Canada. Slavery is not defined only by a plantation economy. Societies in both the Northern U.S.A. and Canada found many profitable places for unpaid slave labour in homes, service businesses, mines, construction, factories and railroads—essentially throughout the entire economy. Both Canadians and Northern Americans grew wealthy from the slave trade and investments in Southern plantations; as in the American South, personal property in slaves—unpaid labour—was a source of great wealth and prosperity for all.

Few Canadians know there were 200 years of slavery in Canada at the same time slavery was raging in the southern part of the Continent. In 1834, the Slave Aboli tion Act ended slavery in the British colonies, including Canada. Contextually then, the 49th parallel was established 12 years after the end of slavery in Canada and 19 years before the American Civil War ended slavery in America. Thus, during the heyday of slavery in North America, American and Canadian slave-holding families, French and English, moved freely back and forth across the Continent with slaves in tow, some compelled by military events and others by residential preference. Families maintained homes and family in both the United States and Canada, a hallmark of the history of many of Canada’s “notable” and wealthy families, many of whom share surnames and family connections with American slaveholders.

Both countries were founded by the same people sharing the same cultures. The question then is, why is it that the United States and Canada maintain very distinct reputations and images today? Canada’s identity is bound up in an odd and continuous colonial connection to the British monarchy. It aligns itself with the Crown as a point of pride and, perhaps, a matter of reputational necessity. It’s a way to strategically distinguish itself from the United States and from a history better known for its massive blood-stained history of slavery. And all the while large swaths of the Canadian population, not the least of which is Quebec, have maintained no special fondness for the English monarchy.

In fact, Canada shares fewer defining elements with Britain than with America. Whether by design or otherwise, the homage to Britain serves to obscure Canada’s greater commonality with the United States, past and present. Canada shares the same blood-stained history. The people of Canada share a culture more closely tied both historically and traditionally to the United States than to Britain.

Why is this important?

Because the myths around American and Canadian culture must be demystified as we prepare to examine, through the writings in this book, the experiences of Black professionals in the charitable sectors of both countries. This is significant because the national context in which Canadian and American fundraisers live and work are more similar than not. And to fully honour and digest the stories shared in this book, we must begin by examining the fiction in both national narratives, and specifically dispel the myths that Canada is historically and socially superior and that Black people are better off in Canada.

The charitable sector is a microcosm of the national culture. In June 2020, The Charity Report noted that, “Charity leadership is almost exclusively white." In Canada, as well as in America, not only do few Black people gain access to leadership opportunities, but also that access is often short-lived due to the oppressive and abusive work culture.

Benevolence, far from fully earned, is conferred gratis on the charitable sector. Its goodness is considered inherent, its intentions and image beyond reproach. But as with the Canadian image, the real identity and behaviour of the charitable sector must be subjected to the light of the truth. As has been the case with Canadian history at large, those who perpetuate the white saviour saga of the charitable sector have routinely erased the voices of Black people. Without the story of Black fundraisers, the documented history of the philanthropic sector will remain barren, incomplete, and given the current thrust of social justice, irrelevant.

A knowledge of these North American realities is critical when engaging with the lived experiences of Black people. These stories are sacred history in the making. They are truth and light. And they serve to correct the current philanthropic record. This is a collection of voices that have been systemically ignored and erased in a sector meant to promote the love of people. These are testimonies of the lives of Black men and women. Their stories are data, the stuff of primary source history.

Fourteen writers from the United States and Canada. We write from the legacy of the same colonialism. The collaboration of the writers serendipitously created an expression of common realities in the charitable sectors in our respective countries. You will be struck by the similarities of our experiences. Our stories should be trusted even as they paint a contrasting picture of the charitable sector. These are the true circumstances in which we write and share the love we find in ourselves and our lives, even in the face of historic and continuing oppression, humiliation and ultimate rejection.

The deep source of our joy is a commodity. It defies our circumstances and is a life-preserver in the deep waters of anti-Black racism. The ability to cultivate joy in the face of pain is a generational legacy passed down through our dna. Our intimate relationship with pain for over 500 years in North America is unparalleled. For centuries Black people have transformed pain into lyrics, music, poetry, dance and visual art for all of society. Our creative expression validates and affirms. It empathizes with all who suffer.

And freedom. This book is freedom. In it we are speaking the truth about our lives, with a hope that the minds and hearts of others will be transformed. With your heart open, walk with us as we unveil the courage we have collected in our lives and our profession. Despite devastating pain, our joy is effervescent and our desire for freedom insatiable. Our love endures.

Nneka is a Black woman, a descendant of the Underground Railroad, an Ojibwa of Anderson Nation, a Momma and a sixth generation Canadian. Born in the ’70s, Nneka was raised during a time of Black power and acute political awareness in North America. As a lover of justice, Nneka has inspired philanthropy as a Fundraising Executive in the charitable sector for the last 20 years. She is the principal and founder of The Empathy Agency, where she helps organizations deliver more fairly on their mission and vision by coaching leaders and their teams to explore the impact identity has on organizational culture and equity outcomes. Nneka is also a founding member of the Black Canadian Fundraisers Collective. She is an author and co-editor of Collecting Courage: Joy, Pain, Freedom, Love.

Nneka’s ultimate joy is her daughter Destiny, an Environmental Scientist working with Indigenous communities in British Columbia. Together Destiny and Nneka continue their family legacy of philanthropic activism in Canada.

Click on the title to buy your own copy of Collecting Courage: Joy, Pain, Freedom, Love

Click on the title to buy your own copy of Collecting Courage: Joy, Pain, Freedom, Love