- Home

- About Us

- The Team / Contact Us

- Books and Resources

- Privacy Policy

- Nonprofit Employer of Choice Award

Part 1 and Part 2 of this series described endowments: their intent, how they work, why they’ve become relatively common, and some of the unintended consequences that can arise over time. In Part 3, we explore other innovative approaches to making impact through philanthropy.

Aligning gift structure with impact horizon

Traditionally, the charitable sector has relied heavily on endowments as one of two default gift structures, leaving donors with few alternatives to consider apart from fully expendable gifts. Before choosing an endowment, donors should first reflect on their philanthropic goals and the time frame they envision for achieving them. Collaborating with advisors and charitable organizations can further align their gift structure with their desired “impact horizon.”

Consider the example of a rural community that lacks access to potable water. A charitable organization may have a credible plan to solve this issue within ten years but lacks sufficient funding. A donor passionate about this cause would likely opt for a fully disbursed gift within the project’s timeline, ensuring the community will gain access to clean water sooner. Endowing a gift for this purpose would extend the project timeline and leave community members waiting longer than necessary.

For problems with longer timelines, (e.g. finding a cure for breast cancer) a different approach is needed. Let’s assume a donor believes a cure could be found within 20 to 40 years. They might consider accelerating research by providing more funding upfront, potentially increasing the chances of discovering a cure within a generation. Spreading out funds for an indefinite period may not be the most effective way to address issues that can be resolved with concentrated efforts.

Annuity or “spend down” funds

When a donor’s desired impact timeline doesn’t align with a fully expendable gift or an endowment, an annuity or “spend down” gift structure, might be the best option. Annuities are typically used by individuals to provide a combination of income and capital over a set period, ensuring financial needs are met throughout their retirement and potentially beyond (through their estates).

Applying this concept to philanthropy allows charities to access funds more quickly. For instance, a $1 million gift could be structured as a 100-year annuity, differing from a traditional endowment. The payout amount of an annuity varies depending on its term: a ten-year annuity might distribute approximately $140,000 annually until its expiration, while a 100-year annuity would yield around $70,000 per year for the duration.

Analysis suggests that annuities are better suited for donors aiming to achieve significant change within a shorter timeframe (less than 30 to 40 years). Conversely, for those with longer-term impact goals, endowments are likely the right choice. That said, care should be taken to ensure the endowment does not become “stranded” (see Part 2 of this series).

Hybrid structures

Some charitable organizations may not proactively present a wider range of gift structure options, but there’s no reason they can’t be explored to align with donor impact goals. For instance, a gift could start as an annuity and later convert to an endowment, or it could involve a term-limited annuity alongside a traditional endowment. This approach is suitable when an organization needs significant upfront funding to launch a new program, followed by long-term support.

A $1 million gift could be split into a $750,000 endowment and a $250,000 five-year annuity. This structure would provide approximately $100,000 annually for the first five years to cover startup costs, followed by a steady flow of $40,000 per year, increasing to nearly $55,000 annually over twenty years and continuing to grow afterward.

Alternatively, for a project that builds gradually and may not need perpetual funding, starting with an endowment that transitions into an annuity might be effective.

For example, a $1 million gift could be endowed initially, generating $50,000 to $60,000 annually for the first ten years. Afterward, as the fund's market value grows to about $1.2 million, it could be converted into a 40-year annuity, yielding around $92,000 per year.

The key is to tailor the gift structure creatively to maximize its effectiveness, ensuring that both the donor and the charity work collaboratively to meet their objectives.

Choosing the right gift structure

There is no inherently right or wrong choice between an endowment, an annuity, or other hybrid models for philanthropic giving. The main concern is that donors are often not fully informed about the available options and their implications. Each approach has its advantages and disadvantages.

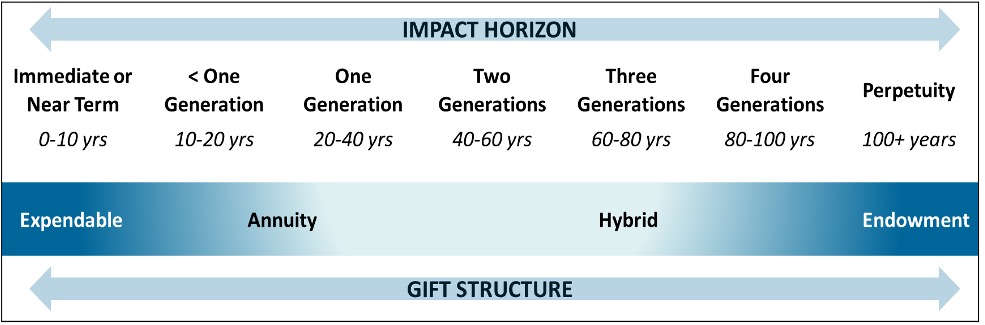

Choosing the right approach is best informed by the donor’s targeted impact horizon, as illustrated here.

If a donor aims to maximize impact within one or two generations, an annuity may be a better fit. For impact extending beyond two generations (considering the lifetimes of children, grand children, or great-grandchildren), an endowment might be more appropriate, provided it is thoughtfully and carefully structured.

Objections and other obstacles

Taking an unconventional approach to giving often meets resistance. This might manifest as organizational “policy” or reluctance to manage annuity funds alongside endowments. While market returns tend to be more predictable over the long term, if a donor is willing to accept the increased risk associated with a shorter investment time horizon, there is no reason an annuity fund cannot be managed in the same pool and enjoy the same annual returns as an endowment.

Some charitable organizations and fund managers welcome the opportunity to work with donors on developing creative gift structures, although others will resist due to tradition, conservatism, or outdated views on effective fundraising.

Some organizations’ policies emphasize goals of preserving capital and driving real growth in fund value (i.e., outpacing inflation). In these cases, the primary performance metric is the market value of the endowment fund over time. This may not align with a donor’s key metrics.

Conclusion

Significant societal issues, such as hunger, climate change, and homelessness, confront humanity today. In North America, there are trillions of dollars tucked away in endowments that could help solve these problems. With an increasing surplus of wealth available now and for successive generations, it’s unlikely that the world will ever run out of money set aside for philanthropic purposes.

Families with the financial capacity and inclination to help others can accelerate the pace of positive change in communities and society. However, established practices may lead to unintended consequences and impact that falls short of potential.

While the traditional approach to endowing philanthropic gifts serves a purpose, donors may drive greater impact and derive more fulfillment by taking a more deliberate approach. By working in partnership with charities and their advisors, donors can align gift structures within the timeframes they wish to see impact made.

There is nothing inherently wrong with establishing an endowment when it’s a fully informed choice. Incorporating mechanisms to ensure it remains relevant, can be repurposed or wound down with clear accountabilities assigned to the parties, can provide some comfort. The key is to start with the “what, why, and when” of giving, not the “how.”

Ultimately, just as we often hear, “You have to spend money to make money,” the same is true for making an impact: you have to spend money to make an impact.

Peter Fardy is Principal, Northport Philanthropic Advisory Services, and former Vice-President, Advancement, Dalhousie University.